Charter Schools: Deliverance or Distraction?

- Theresa Capra

- Jun 25, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 30, 2020

Remote learning has shone a spotlight on the steep inequities in our schools. For decades, policymakers and politicians have debated the best ways to reform, or improve, educational outcomes for historically underserved groups. From unfunded federal mandates such as No Child Left Behind, to the current school choice movement embodied in charter schools--sometimes it takes a pandemic to remind us the issues are bigger than what's on the surface. #remotelearning #Covid19 #charterschools #theresacapra #research

Charter schools: a vision gone wrong

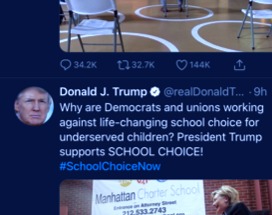

A Wall Street Journal opinion titled Charter Schools’ Enemies Block Black Success (June 18, 2020) highlights opposition to charter schools leveled by teachers’ unions and democratic candidates who rely on their support. Donald Trump tweeted in response, “why are Democrats and unions working against life-changing school choice for underserved children?” Not surprisingly, the President exaggerates the issue by defining charter schools as “life-changing” while claiming that teachers’ unions wish to prevent improved educational outcomes for underserved populations.

Usually democratic positions tend to favor programs that support historically marginalized populations, and charters have even enjoyed bipartisan support during their history, so why the spike in hostility? Of course politics muddy the waters of altruism on all sides, but “life-changing” is far from an accurate description of charter schools, and unfortunately whether or not to expand them is political posturing that’s not truly about students.

First and foremost, charter schools in practice ARE NOT in line with their original intent. In 1988, Al Shanker, the then president of the American Federation of Teachers, delivered a speech on an idea to form laboratory schools that would serve as beakers for pedagogical experimentation to identify and roll out best practices --the scientific method applied to teaching and learning in autonomous schools. He referred to these institutions as “charter schools,” and soon after the state of Minnesota moved on this idea and established the first charter by 1992.

But instead of experimental studios, charters ended up promoting a different reform ideology—competition. Milton Friedman, a Nobel-Prize winning economist, postulated that competing for students would force public schools to improve because if they didn’t, similar to businesses, they would shut down. Many states enacted voucher programs where low-income families could attend private schools, including religious ones, as a recuse net from failing public schools. Theoretically, public schools would step-up their games for fear of becoming obsolete while in the meantime, some low-income students could escape through an open window.

Vouchers, however, have been fraught with constitutional debate since their inception because of the potential entanglement between church and state. In fact, a recent decision from the SCOTUS examined whether or not students may attend a religious program with public dollars in in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue. The Court decided in this case it was permissible, but voucher program continue to cause tensions.

Are charters really about choice?

Charter schools are devoid of any religious issues and they are technically public schools, so they move the discussion squarely on how to improve public schools in low-income areas--spend more, or find an alternative. Charters are funded by tax-dollars but are privately run, and when an entity, which could be a celebrity, receives a charter, or contract from a board of education, they operate with relaxed oversight and regulation in exchange for the deliverance of higher achievement and better social outcomes for students.

Accountability for results can be enforced because school boards reserve the right to shut them down. Parents can choose to apply to any charter and if there are more applicants than seats, state laws require lotteries for admission.

Charters mostly open in economically disadvantaged areas for an obvious reason—that’s where they’ll find patrons because the local public schools are failing due to high poverty and community atrophy. A holder of a charter can choose to hire a private company to manage the school and such companies are in the business of making a profit.

Putting this all aside, a major problem with the charter debate is that many people do not judge them in practice but instead have come to perceive them as a movement synonymous with “choice,” which has a nice American ring. So if you disagree with charters in practice, you’re anti-American. However, a more accurate depiction is that charters reflect the enduring argument over which social agencies should be public and which ones should be private.

It’s not very different from arguments about whether or not all Americans should have access to health insurance, whether social security should be privatized, or whether college tuition should be subsidized by states and the federal government. Charters, although they were not originally conceived for this purpose, invoke the belief that private entities can do better than local school districts. Accordingly, an important question to consider is whether or not this private model is better than investing more in public schools. We should be able to answer this question regardless of political debate--after all, they've been around for over 25 years, operate in almost all 50 states, and serve more than 3 million students.

Are charters living up to their promise?

A literature review of charter performance turns up both positive and negative reports. For example, some such as KIPP have an impressive track record, while others in the state of Pennsylvania are described as horrible and rebuked for widespread fraud, absence of accountability, and inconsistent results in the best cases. States such as Florida that are particularly struggling to provide an adequate public education to their residents have been faced with research that demonstrates their charters are at best a wash--no better, no worse.

The National Education Association, which has been an ardent critic of charter schools, points to research released by Stanford University in 2019 (and earlier) that demonstrates charters throughout the United States are not living up to their promise of better academic outcomes.

Of course research is vulnerable to bias depending on viewpoints preferred, but still, it’s likely a fair assessment to say that overall, most charters are not faring much differently than their public counterparts.

Given that charters have tremendous autonomy and freedom from the purported nuisances typically cited for public school failure (unionized teachers, state tenure laws, state oversight of curriculum), it’s surprising that they’re all not knocking our socks off.

Despite longer instructional days that have been found to benefit the neediest students, they are not providing a pedagogical metamorphosis and many copy the methods of the local public schools. Simply having the choice to attend a charter is clearly not enough to change the lives of poverty-stricken children and we are seeing this firsthand with uneven outcomes stemming from remote learning.

The implications of the charter model

Charters are not really about school choice. Charters are basically more public schools in low-income areas that are attractive to families because they have smaller classes, longer school days, or sometimes it could be as simple as they require uniforms, which projects an air of discipline. But let’s say a minority family wanted to “choose” to send their child to the public school in an affluent neighboring town--the answer would be no.

Local towns run their local public school districts and the higher the property tax bills, the better equipped the schools. Families in wealthy, affluent, mostly white, suburban districts are not clamoring for school choice, nor are wealthy urban families who do not use the public schools in the first place. They are perfectly content with the system. And they already have plenty of choices--they can choose elite private schools, homeschooling, personal tutors, or prepare their children for competitive magnet schools.

A real school choice movement would be looking to topple zoning all together, as well as local control. Open up township borders and let low-income black and brown children in. If charters can find spaces to squeeze into in urban areas I’m sure towns could get creative. Or perhaps the states could rezone and combine districts to provide more choice. But we’re not talking about that.

Charters are more about the privatization of public schooling and suppression of local control in economically disadvantaged areas. The presumption being that these poor, mostly minority communities have failed at public education so it’s time to let private companies driven by profit clean up their messes.

And even though charters have demonstrated inconsistent results at best, the logic is that local school boards should be persuaded to allow more of them to operate with greater autonomy than their public schools while simultaneously straining precious resources. This would be considered an act of war in wealthy towns. Businesses have to jump through hoops to open up in many insulated municipalities.

Charter schools are not rescue crafts saving poverty-stricken children from sinking into the depths of their failing public schools. They are a distraction from the true storms --inequity, poverty, decades of discriminatory policies such as segregation and redlining. Educational reform in high need districts must be linked to government efforts and spending on reducing poverty.

There’s a reason why so many charters are not producing amazing results--the students still live in economically stifled communities with limited access to technology, proper health care and nutrition, as well as other stressors that would burn any adult out in a flash. And even though there are some outstanding charter schools, there are also successful local public schools in high-poverty areas.

Simply expanding charters despite their mixed results is like crossing your fingers and hoping for a win. If charters are doing better because of longer school days, negotiate that with teachers' unions. If smaller classes are key, then direct resources towards that.

Reform efforts should focus on improving public education for all students, not simply tossing life preservers to a few lucky ones who get into the high performing charters. Haven’t we learned anything from the Titanic?

Additional sources:

Comments